Beech Book is poem 8 on the Westonbirt Arboretum Autumn Trail 2017. I met one of the Barnett family who had adopted this tree for the family's "roots, shoots and future saplings."

This poem featured at two other sites - The Kymin and Dartington Hall. Two lines in the poem are site-specific so I rewrote them for the other installations (see below).

The audio version of the Westonbirt version was read by Chris Beale.

Beech Book

This tree knows all the thoughts of people passing

and parcels each in paper leaves to hold,

so every word is weighed and counted, massing

a sympathy of fractured stories.

This path a wash of jumpers, skirts and anoraks:

muddy and wind-torn, hemmed and zipped, loose and free.

Bonnets skip in front of strolling top hats;

behind, Celts in cloaks kneel to Fagus god of beech.

This arboretum – a library of trees –

curates the pages from lives of passers by,

connects their prints within the rings of heartwood

and in the quiet reads every line.

So all the knowing on the Silk Wood trail

nurtures stillness, here for us to find.

From the collection 'Conversations with Trees'.

© Marchant Barron, 2017.

Beech Book - The Kymin

This tree knows all the thoughts of people passing

and parcels each in paper leaves to hold,

so every word is weighed and counted, massing

a sympathy of fractured stories.

This path a wash of jumpers, skirts and anoraks:

muddy and wind-torn, hemmed and zipped, loose and free.

Bonnets skip in front of strolling top hats;

behind, Celts in cloaks kneel to Fagus god of beech.

This once coppiced hill – a library of trees –

curates the pages from lives of passers by,

connects their prints within the rings of heartwood

and in the quiet reads every line.

So all the knowing on the Kymin

nurtures stillness, here for us to find.

Beech Book - Dartington Hall

This tree knows all the thoughts of people passing

and parcels each in paper leaves to hold,

so every word is weighed and counted, massing

a sympathy of fractured stories.

This path a wash of jumpers, skirts and anoraks:

muddy and wind-torn, hemmed and zipped, loose and free.

Bonnets skip in front of strolling top hats;

behind, Celts in cloaks kneel to Fagus god of beech.

This garden – a library of trees –

curates the pages from lives of passers by,

connects their prints within the rings of heartwood

and in the quiet reads every line.

So all the knowing leafed in Dart-born trees

nurtures stillness, here for us to find.

Marchant's Notes on 'Beech Book' for Westonbirt

This lone beech stands at the end of the Silk Wood trail. Originally, I was given the larger beech further down the hill which is both tall and wide enough to support a sonnet.

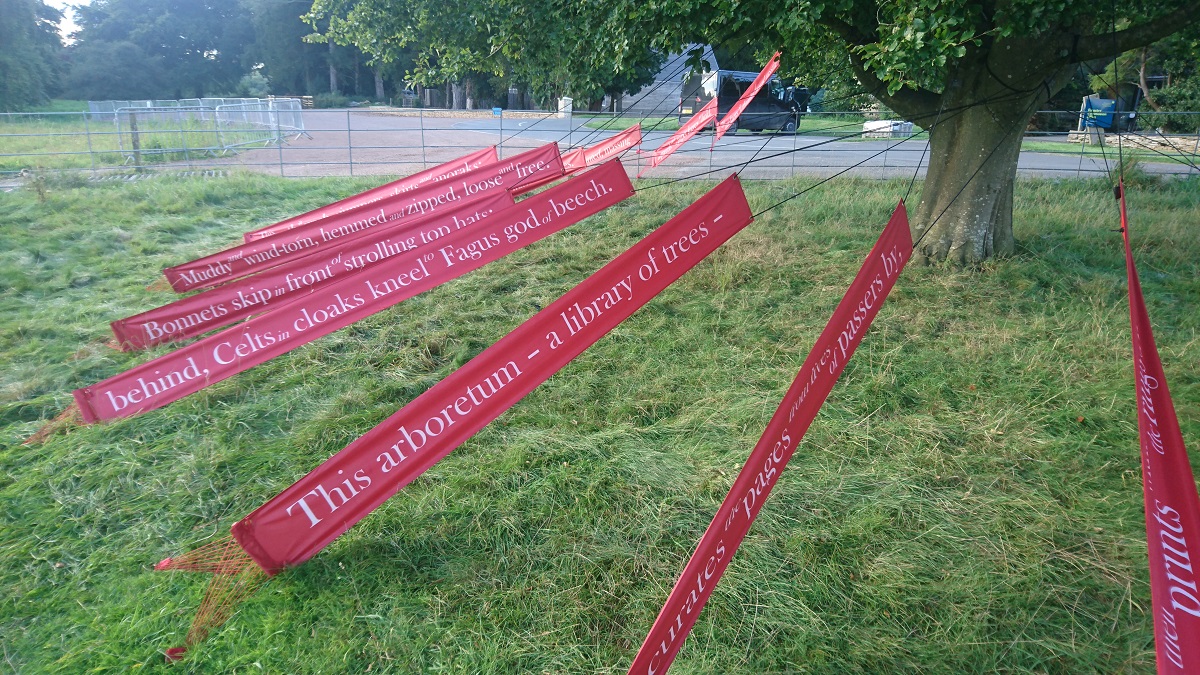

I still wrote a sonnet as this is a tree I wanted to fill with words. But the banners had to be arranged in a swirl around the tree, rather than hanging vertically.

The leaves of the beech turn brown in winter and are held onto for longer than other trees, sometimes not falling until early spring.

I looked at how people wandered by this tree and this sparked my idea for the poem:

The tree knows all the thoughts of people passing and each thought hangs in the paper leaves and each feeling is written on bark and into books. But when leaves fall, the thoughts seep into soil which feeds the wisdom of the tree.

I knew that other poets would be moved by trees and researched what wisdom others had found. The words of Hermann Hesse resonated loudly:

"Trees are sanctuaries. Whoever knows how to speak to them, whoever knows how to listen to them can learn the truth … when we are stricken and cannot bear our lives any longer, then a tree has something to say to us: Be still! Be still!"

Jackie Kay’s 'The Kindness of Trees' also spoke to me:

"One to keep the bright light glowing,

A song of what we know without knowing."

So I ended my poem thinking of how trees help us and that is the message I wanted people to leave with:

"So all the knowing on the Silk Wood trail

nurtures Stillness, here for us to find."

The beech is synonymous with writing and books. The bark of beech is smooth and pale and was used to carve on. These carvings are called 'arborglyphs'. In my poem, I had written “Behind, Celts in cloaks carve their runes in beech” but, understandably, Westonbirt thought this may encourage some modern day carvings.

In Germanic societies, before the use of paper, beech wood tablets were used. The etymology of the words 'beech' and 'book' are connected. The Old English boc meant 'beech' but also meant 'book'. Today, in German, buch means 'book' and buche means 'beech'.

Celts had their own symbol (from the ogham alphabet) for the beech or 'phagos' as it was known. Fagus sylvatica is the Latin for 'beech'.

This link between writing books and the beech gave rise to the line in my poem, “This arboretum – a library of trees”. But like any other poet in writing, there are many lines that get thrown away for example:

“Ribbons of ink wrap the roots from the dreams

That rock the leaves when they are born.”

Druids venerate trees and for them the beech is the holder of lore, learning, ancient knowledge and tradition. They associate the holding of leaves in winter to the holding of wisdom when we reflect more in winter.

Beech is associated with femininity and is known as the queen of the forest. Some beech trees can live for over one thousand years.

These lines from other poets inspired my writing:

“In the late spring/ You come out plain/ A brown paper wrapper” – Peter Bormuth, Tricolor.

“Out of a book, which now you think of it/ Is one of the transformations of a tree” – Howard Nemerov, Learning the Trees.

“Lengthen night and shorten day/ Every leaf speaks bliss to me” – Emily Bronte, Fall, Leaves, Fall.

“These are not leaves of grass/ But leaves of Heart/ Leaves of Soul” – Bijay Kant Dubey, These Are Not Leaves of Grass.

“They will not go. These leaves insist on staying” – Elizabeth Jennings, Beech.

“like snowflakes falling on the Flemish clay” – Margaret Postgate Cole, The Falling Leaves.

“They are a whole neighbourhood of/ Descended voices …/ Their words have been spoken/ In communion …” – Diane Shishido, The Words of Trees.

“Where trees speak words/ And riverbeds are laved with gold/ … Where can all this exist?/ Here, as long as I don’t resist” – Christopher’s Dead, Where Trees Speak Words.

“Deep in the forest there stood

A tree whose heart beat in the winter wood

Who understood everything that was bad

And everything that was good.

(…)

And people gathered round the tree:

To sing the winter song, in harmony;

One to keep the bright light glowing,

A song of what we know without knowing.” – Jackie Kay, The Kindess of Trees.

Silkwood Trail Display Board

By Ben Oliver

Once upon a tree: Words for writing in other languages also highlight woody links; the Latin liber (the root of library) is believed to have originally come from the word for bark.

The fact that old writings survive today is often thanks to ink used to write them down. And again trees play their part; arguably gall ink made from oak galls (small plant growths caused by parasitic insects found on many species of oak) is the most important ink in Western history. Gall ink contains acidic tannins that actually bite into the paper, making the ink virtually impossible to erase. Many of our cultural treasures were written using gall ink because of this indelibility; from Da Vinci’s notebooks to music scores by Bach and drawings by Van Gogh.